Questioning the Kittens - The Misstranslation of Medicine

Medical history contains some of the most astonishing accounts. We commonly look patronizingly back on our forefathers with pity when reading about their wild, whacky tinctures, elixirs, or any variety of alchemical arrangements. On account of this, a certain precedent or acceptance has come into fashion where the average person simply assumes absurdity.

This, I believe, is quite a problem. Misinterpretation can lead to misrepresentation of historical sources and false conclusions regarding entire compendiums of knowledge. Imagine, simply imagine, that your life's work concerning medicine, concerning the very holy inner-workings of the human body, is viewed by posterity as purely juvenile nonsense. Or perhaps, simply misunderstood and left burdened by dust, degrading on the shelves of lowly apothecaries, left to depixelate in online collections.

Personally, I would be livid. Therefore, I felt uniquely impassioned to sort out a singular quote which has been flying around the internet stemming from one of Germany’s first medical texts.

Lorenz Fries was a renowned German physician active in the 16th century and supposedly recommended the following remedy to alleviate gout:

“Roast a fat old goose and stuff with chopped kittens, lard, incense, wax and flour of rye. This must all be eaten, and the dripping applied to the painful joints.” - Lorenz Fries (featured in Tasting History with Max Miller).

Hä? Now, I don’t believe that for a second.

I first learned of this quote while watching Tasting History with Max Miller on YouTube (absolutely fantastic channel). The famed FoodTuber himself questioned this quote; but being unable to find the original asked the audience if anyone would be interested in a little… Research.

The original translation seems to be lost to the aether, which means only the original is available online or easily accessible. Most news sites offering citations either reference other websites, or even more strangely and questionable, the original text itself. Hm, how many American reporters can read 16th century German? Not many, maybe five.

Safe to say I was completely überzeugt and aufgeregt; thus I resolved to lend a hand in this great endeavour to determine, truly, if kittens cure gout.

And so began the search for truth.

METHOD

SCHRITT EINS / STEP ONE

First of all, vor allem: What am I looking at?

In order to answer this question, I needed a suitable online source. I eventually found a very clean, neat PDF from the Universität Heidelberg.

The specific text from Heidelberg was a copy from 1519, written in what appears to be Schwabacher, the font preceding Faktur. However, I believe the text represents a period in transition as many letters are printed with a flourish found in both sorts.

All right, nice. Font fest, now onto the next part: actually reading it. I pride myself in having an eye for handwriting or antiquated printing, as my own hand is quite difficult to read (count yourselves lucky this is typed) and sometimes have to decipher my own notes.

After about four hours of staring at the scribbles stamped upon the bleached pages, I was able to find a modern pairing for every old letter or contraction. Given the occasional use of Latin terminology, the text flows through various dimensions of language, requiring either competency or merely patience.

Luckily, I possess both though needed to absolutely exploit the latter, in this context.

Text now readable, lesbar; I could truly begin sifting through every aged page. I was quite ready to undertake this next step then suddenly realized: Wait, what do I really know about gout?

SCHRITT ZWEI / STEP TWO

Well, I don’t know a whole lot, aside from the content within the condensed, quality history piece from Max Miller. So, I needed to learn a bit about medicine.

What did they know about gout?

“Ow, my toe hurts when I consume egregious amounts of alcohol, meat, and sugar-rich foods.” - A good number of kings.

Actually an astounding amount. No need to go into detail here about that: this is an article about language!

What did they even call gout back then?

Hm, well:

Modern German: die Gicht

Old-er German: gegicht, gegight, dermgegight/gegicht

Latin: Gutta

Ancient Greek: Podagra*

*namely gout of the foot.

Colera was referenced as well within certain sections pertaining to gout, at least within Fries’s treatise. In the section out of which the quote stems, he describes etymology and foundation of the affliction itself.

Now armed with the proper vocabulary, background, and etymological knowledge: the slog ensued.

I initially began by searching every chapter which touched upon certain ailments or symptoms associated with gout. The problem, of course, is that gout affects many different parts of the body; many sections include some elaboration upon cures for one illness which then apply to those certain sufferings associated with gout. That took forever, but eliminated a large portion of the text.

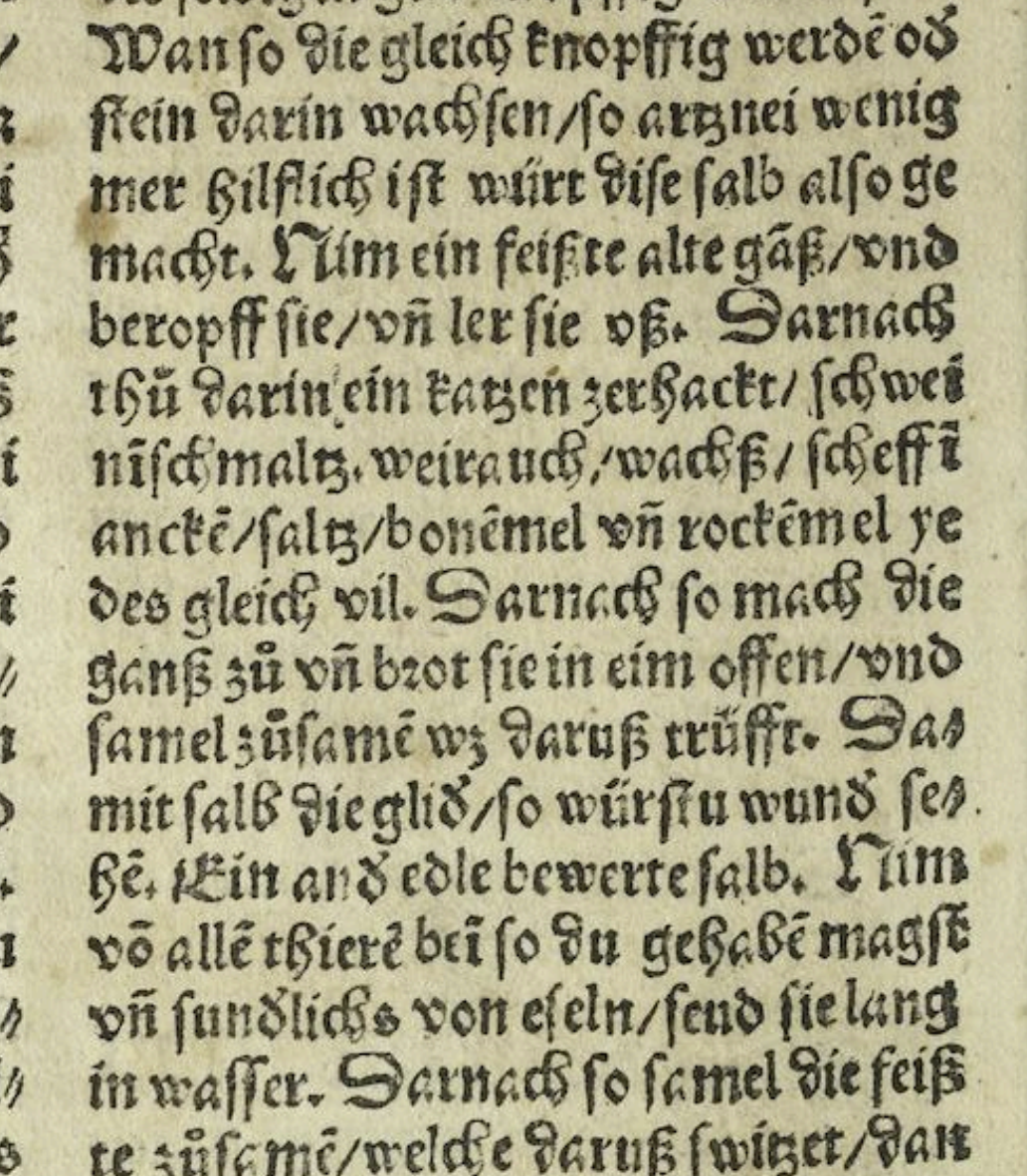

Then one day, after more hours than I dare to recount here, I found the quote itself:

The infamous miracle cure.

Crazy, yeah? The text (in broken, somewhat modern German) reads as follows:

“Nimm eine fette alte Gänse

und berupfe sie

und leere sie aus.

Danach, tue darin ein Kätzchen zerhackt /

schmeiß nicht Schmalz,

Weihrauch / Wachs / einen Scheffel Anke / Salz / Bohnenmehl und Roggenmehl

je des gleichen viel.

Danach so mach die Gänse und brat sie in einem Offen /

und sammele zusammen was daraus tropft.

Das mit (damit) salbe die Glied(er) /

So wirst du den Wund seichen (harnen).”

- Lorenz Fries (1519)

A quick gloss may be in order:

Berupfen berupfte berupft - to quill a bird.

Der Scheffel - a certain measurement used in recipes.

Die Anke - old word for butter.

Seichen seichte geseicht - essentially: ‘to let urine, bile, or goo out of a wound or body part’. In this context he’s referring to-what we now know-is uric acid.

And the word, the kittens themselves: Kätzchen. Well, in modern German that definitely would be ‘kittens’ or kitten (diminutive remains the same in the plural). We’ll come to that in a moment.

So, I suppose my translation in English would read something like:

“Take a fat old goose

And pluck all the feathers,

Remove all organs, so that it is then empty.

Afterwards, put a minced (Kätzchen) inside,

Do not throw out the lard, then comes:

Incense, wax, a scheffel butter, salt, flour of bean and rye

The same amount of each.

Afterwards prepare the goose then roast it in an oven

And gather together all the drippings.

With this you may salve the limbs

So will you remove the fluid from the wound.”

- Lorenz Fries, übersetzt (1519, 2025)

I haven’t translated Kätzchen, because that’s the complicated part. However, some differences already appear in comparison to the first English translation.

SCHRITT DREI / STEP THREE

First of all, the previous translation is much shorter, providing a very condensed version of the actual cure. Curious, that they chose to widdle it down to a mere two sentences.

Second, the instruction to fully consume or einverleiben the complete mass of goose-cat. Nowhere in this excerpt does any direction exist, recommending the voracious, total envelopment of the dish.

Then lastly: the addition of kittens. There are several problems that appear almost immediately when reading the full delineated direction:

Save the ‘lard’ from the kittens. He mentions the lard, Schmalz of this animal in an earlier section as well. So the fat is important. Weird, though, that an animal so lean as a kitten should be lauded by a renowned physician for fat content.

Cats weren’t really used in European Gastronomy within this time span.

Other animals were available to farmers, common people, or royalty.

So we arrive again at the contested point, the most disputed, heated peak of this grand investigation. What does he really mean by Kätzchen?

I searched for quite awhile for any dialectal oddities in the regions where Lorenz Fries was active. Certainly some exist, but none are worth mentioning here. So this was somewhat of a dead end. Though, considering the use of certain words to describe other processes, remedies perhaps, gave me an idea.

What does he instruct the reader to do with the drippings? Make a salve.

Now: Lorenz Fries was born and partially active in the southern regions of Germany. There is one animal they do use in the south to produce a certain salve to mend disease of the skin; gout included.

And lucky me: they refer to them partially as Katze/Kätzchen.

Enter: The Groundhog / Murmeltier

ERGEBNIS / RESULT

The solution was hiding in a hole, tucked away high in the Alps the whole time. Groundhogs are commonly found in the South of Germany and there, during certain seasons, hunted. Female groundhogs are referred to as Katze or Kätzchen, sometimes they are just referred to in general with these terms. Today, people in these areas still make salve out of the fat as natural remedies for many diseases. Several producers state there being a longstanding tradition of, well, grounding groundhogs into salve, so to speak.

My theory then, would simply be that Lorenz Fries is actually referring to groundhogs instead of kittens.

, I wanted to make this public. Send the truth unto the masses, clearing the name of Lorenz Fries. Ending finally, this kitten catastrophe which has plagued the internet for the past few decades.*

*This will be reposted as well once I change this website up a bit, though the link should still work. The site itself may be down for a short time.

- DS